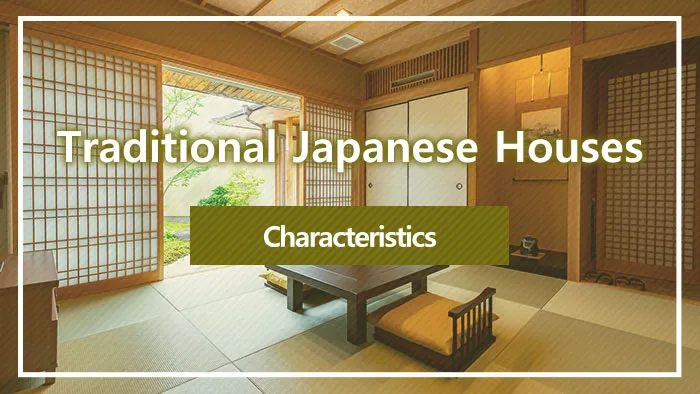

When visiting Japan, you may notice traditional houses scattered throughout the modern urban landscape, evoking a sense of nostalgia and warmth. The solidity of tiled roofs, soft light filtering through shoji screens, the fragrance of tatami mats, and seasonal views from the engawa veranda—all reflect Japanese wisdom and aesthetic sensibility for living in harmony with nature.

This article examines the characteristic elements of Japanese houses and explains the functional and cultural significance of each. Understanding the depth of Japanese architecture, which differs from Western-style construction, will enrich your experience when staying at traditional farmhouses or hot spring inns during your travels.

1. What Are Traditional Japanese Houses?

「東京国立博物館」敷地内の一般公開されていない貴重な日本家屋「応挙館」がカフェに🍵https://t.co/CSlPva1htK pic.twitter.com/3b1jGLW1ba

— Time Out Tokyo JP (@TimeOutTokyoJP) August 15, 2023

Traditional Japanese houses are called “minka” and refer to residences where farmers, merchants, and craftspeople lived. While architectural styles vary by region, they share a common emphasis on harmony with nature and the soft incorporation of light and wind through tatami and shoji. Additionally, they are characterized by wooden construction and the integration of living spaces with gardens, allowing residents to experience the changing seasons.

Representative architectural examples include machiya townhouses in Kyoto, gassho-zukuri houses in Gifu Prefecture’s Shirakawa-go, and traditional farmhouses remaining in Nagano Prefecture’s Kiso Valley. These well-preserved structures continue to convey Japanese lifestyle and aesthetics to visitors through tourism and accommodation experiences. Even in modern homes, elements such as genkan entrances and small Japanese-style rooms carry on this tradition, reinterpreted as contemporary Japanese-style living spaces.

2. Characteristics of Traditional Japanese Houses

\3/18(土)12:00~放送予定/#フジテレビ #有吉くんの正直さんぽ が #足立区 に!

— 足立区役所 (@adachi_city) March 17, 2023

戦前に建てられた日本家屋、千住の文化サロン #仲町の家 も登場!

どんな「正直」が聞けるか!?気になりますね!

土曜の昼は「有吉くんの正直さんぽ」をお楽しみに!

シティプロモーション課でした!#北千住 pic.twitter.com/WBZGfD0QcK

Japanese houses are fundamentally wooden structures that utilize natural materials, offering the appeal of experiencing the changing seasons. Elements such as tatami, shoji, genkan, and gardens harmonize together, cherishing aesthetics and spirituality in daily life. Here, we introduce the characteristics of traditional Japanese houses.

2-1. Genkan

The genkan is the entrance to a Japanese house and an important space for welcoming visitors. Above the entrance is a small roof called a hisashi that protects the house from rain and sunlight. The doma is a space for removing shoes, serving as the boundary with the clean interior.

Beyond this is a raised wooden platform called a shikidai, which serves to welcome guests and bridge the height difference from the doma. There is also a step called an agari-kamachi, where the custom of removing shoes before entering the interior originated.

2-2. Kusari-doi

Kusari-doi is a uniquely Japanese type of rain gutter. While ordinary downspouts are pipe-shaped, kusari-doi consists of chains formed by linked rings or petal shapes, allowing rainwater flowing from the roof to travel down the chain to the ground.

In addition to the practical function of draining water and protecting the building, it offers the distinctive feature of allowing people to visually enjoy the flowing water. It has been used in temples, shrines, and Japanese-style architecture since ancient times. It is a uniquely Japanese building element that allows people to enjoy seasonal rains as atmospheric elements.

2-3. Tokonoma

The tokonoma is a special space set aside in one corner of a Japanese-style room for displaying decorative items.Initially, it was used as a place to enshrine Buddhist statues and implements or to entertain people of high status.

Over time, its role evolved, developing into a space for displaying hanging scrolls and flowers to express seasonal feelings. While few modern homes include them, the tokonoma remains a symbolic element of Japanese-style rooms, preserved as a space embodying Japanese cultural aesthetics.

2-4. Tatami

Tatami is a flooring material that symbolizes Japanese life, and its raw material, igusa rush, has grown wild in various parts of the world since ancient times. In Japan, it was used early on as matting and later developed into special tatami used by royalty as bedding.

Subsequently, it became associated with the tea ceremony and traditional architecture, and the style of covering entire rooms became common. The fragrance and soft texture of igusa rush are pleasant, and tatami remains cherished today as an element supporting Japanese culture such as the tea ceremony and judo.

2-5. Shoji

Shoji are uniquely Japanese fixtures consisting of wooden frames covered with Japanese paper. They partition spaces while also serving as walls. The prototype was a sliding door used on the exterior of shinden-zukuri architecture, which later developed into akari-shoji that allows light to pass through. It subsequently spread to samurai residences, and kumiko latticework was refined, giving birth to diverse designs.

Japanese paper blocks outside views and wind while softly diffusing light, making Japanese-style rooms bright and tranquil spaces. Excellent for humidity control and heat retention, shoji are fixtures that have supported Japanese life.

2-6. Engawa

The engawa is an architectural element unique to Japanese houses—a wooden-floored passage-like space connecting rooms and gardens. Similar to a wooden deck or veranda, it is characterized by its ambiguous positioning, neither inside nor outside.

Here, people can sunbathe, enjoy evening coolness, or moon-gaze while experiencing nature throughout the seasons. The engawa is one innovation that improves ventilation in summer and captures sunlight in winter. It has been cherished not only for its utility in energy conservation and comfortable living but also as a place for interaction among family and neighbors.

2-7. Ofuro

山梨「古民家宿るうふ」書之家&丘之家がリニューアル、蔵の檜風呂や地元産ワインを堪能#山梨 #旅行

— 女子旅プレス (@mdpr_travel) September 3, 2021

▼写真・記事詳細はこちらhttps://t.co/8pw02KMj8f pic.twitter.com/Gn0keYzO62

Japanese bathing culture spread as an act of purifying the body under Buddhist influence. It began with steam bath facilities at temples, which were eventually opened to commoners and developed into public bathhouses called sento. As time progressed, wooden tub baths and goemon-buro appeared, and bathing habits penetrated households.

Characteristics include the custom of washing before soaking, which emphasizes cleanliness, and slowly immersing oneself in relatively hot water of about 41–43 degrees Celsius. Today, home baths have become common, and diverse styles such as hot springs and super sento are enjoyed.

2-8. Fusuma

【明日も一般公開を実施】

— 内閣府京都迎賓館 Kyoto State Guest House (@Kyoto_Geihinkan) February 28, 2025

明日もガイドツアーを実施いたします

9:30~ 清和院休憩所にて当日整理券を配布いたします

全ての回、ご予約に空きがございますので、

皆様のご参観をお待ちしております

襖は一見、無地のようですが、灯りに模様が煌めきます#京都迎賓館 #唐紙 #kyotostateguesthouse pic.twitter.com/ZriYrtviSV

Fusuma are uniquely Japanese room dividers—fixtures made by attaching paper or cloth to lightweight wooden frames. They are easy to open and close, allowing flexible changes to floor plans, and are characterized by the freedom to expand or partition spaces as needed. Japanese paper regulates humidity and has the effect of keeping rooms cool in summer and warm in winter, making it a structure suited to Japan’s climate.

By replacing the surface paper, the room’s atmosphere can also be changed, and fusuma have been widely used in closets and guest rooms. Today, design diversity has also progressed, and they are cherished as fixtures combining tradition and practicality.

2-9. Irori

11/25(土)・26(日)【#紅葉とたてもののライトアップ】開催!https://t.co/AV5ZhBHm5p

— 江戸東京たてもの園 (@tatemono1) November 14, 2023

民家の炉焚き|16:30~19:20

西ゾーンの農家「吉野家」「綱島家」の囲炉裏に日替わりで火を入れます。#たてもの園 #紅葉 pic.twitter.com/vFC24UJXw3

The irori is a traditional Japanese heating and cooking facility—a hearth where the floor is excavated and filled with ash, and firewood or charcoal is burned. Family members and guests would gather around the fire to enjoy meals and conversation, making it the center of daily life. Additionally, the smoke served to protect wood from insects and decay and to dry thatched roofs.

With a history of supporting regional industries such as sericulture and gunpowder ingredient manufacturing, the irori is an entity combining practicality and cultural symbolism. While no longer a necessity in modern life, it has been preserved as a space for enjoying special experiences.

2-10. Kawara Roofs

Kawara roofs are traditional Japanese roofing materials. Made by firing clay at high temperatures, they are extremely durable and long-lasting. They not only soften the sound of rain but also excel in insulation and fire resistance, making them building materials suited to Japan’s climate and lifestyle.

Introduced from China, they were used in temples and aristocratic residences before eventually spreading to commoner homes. They were subsequently valued in urban areas as fire prevention measures. Today, regional tile cultures such as Sanshu kawara, Sekishu kawara, and Awaji kawara continue to thrive.

2-11. Gardens

Japanese gardens are designed to skillfully recreate nature while harmonizing with buildings, bringing tranquility and beautiful scenery to residences. Representative styles include karesansui, which expresses landscapes with rocks and sand; chisen-kaiyushiki, where one enjoys walking around a pond; and tea gardens that lead to tea rooms.

Gardens feature elements such as pine trees, maple trees, moss, stone lanterns, and stepping stones, and are also characterized by allowing one to feel the changing seasons. Today, new gardens combining lawns and BBQ spaces have emerged, cherished as spaces fusing traditional beauty with modern lifestyles.

Summary

Traditional Japanese houses are not merely dwellings but embody the living culture of Japanese people who live in harmony with nature. Elements such as the hisashi and doma of the genkan, tatami and tokonoma of Japanese-style rooms, fixtures like shoji and fusuma, and gardens and engawa have supported comfortable living while reflecting the seasons. Gatherings around the irori and bathing in the ofuro have also been passed down as places deepening interaction among family and companions.

When traveling to Japan, you can actually experience traditional Japanese spaces and culture by staying at traditional farmhouses, machiya inns, temple lodgings, or hot spring inns. By encountering the traditions of Japanese houses, you can feel the aesthetics and spirit of “wa” (harmony) that permeate daily life.

*This article was created based on information as of October 2025.